I am flat out suspicious of adults who ride bicycles. Not that I am proud of this fact. I just want to own up to it from the start. I should also add that I am an adult who owns and on occasion rides a bicycle. This last bit of information I throw in to underscore my self-awareness that hypocrisy and prejudice are not strangers, they are bedfellows.

Where I grew up adults didn’t ride bicycles. In the late 50’s and early 60’s kids rode bikes. And although we rode them everywhere, I don’t recall ever thinking of them as modes of transportation or even exercise equipment. They were just bicycles. The thing most kids did. It was our medium and connector. Kind of a crank and chain powered Facebook.

For us transportation implied an attached motor and exercise came by working for a living. My father tolerated bike riding if you were a child. But that faded as you grew in age. By puberty when, in his mind, you should begin to start contributing to your own keep, he was known to boil over on this topic at times.

His rant was usually along the lines of, “Look, if you can’t find something more productive to do than ride your bicycle all day I would rather you just lock yourself in your room. If you want to be a goof off fine, just spare me your advertising the fact all over town.”

It stayed with me. Today when I see an adult riding a bicycle my mind runs along one of two long established paths. The first — there goes a person who has too much time, money, and calories to burn. Can’t they find something more productive to do? Or, if they are pedaling along without thousand-dollar biking togs I think — there goes someone who has lost everything and is reduced to transportation by child’s toy. How sad… Please don’t break into my house! The first type makes me angry, the second makes me guilty and anxious. I am not a good witness to others fortune or their misfortunes. Leave me to my own, thank you very much!

Recently my wife and I realized a lifetime dream and purchased a travel trailer. After a snowy 250-mile cross Cascade drive to bring it home I discovered I had under-estimated the size of the required storage facility and over-estimated my rusty backing skills. When that reality became unavoidable, I resigned myself to the fact that, for the night at least, I would have to park it on the dead-end street in front of our house. A matter that would require maneuvering the combined 47 foot truck and trailer in reverse, downhill, for a block on a dark and now snow slicked road.

Growing up farming backing large and often oddly shaped trailers was a required skill. It became second nature and I prided myself on being quite good at it. Something my daughter struggled to believe, having gamely stood in the wet cold for a considerable length of time trying to safely guide me down the street. On what must have been the 10th but more likely the 20th attempt I once again lined up and made a quick scan down the street I was blocking. While thankful there were no headlights, I did pick up movement a block and a half away. It was a sole bicyclist. Even from the distance you could see it was likely a single gear curb crasher, no lights, no reflective clothes, no helmet, a growing black shape pushing itself into focus through the blowing snow.

As bike and rider approached, it glided through the full illumination of my headlights. Rather than continuing down the street, however he made a sharp turn and pulled up next to my open window. Slipping off the seat to straddle the cross bar was a man who appeared to be in his late forties or early fifties. Dressed in well-worn winter coveralls or perhaps a snowmobile suit, knit cap, and gloves. He was thin, tall, fit and had a friendly face and open manner.

“Where you headed with this thing?” he asked. I said I needed to get it down in front of my place for the night and given the conditions I was being extra cautious. An answer that while technically true, glossed over the obvious fact that from the outside it looked an awful lot like I didn’t know what I was doing. He smiled reassuringly and gave me that special nod that truly stand-up guys give when they recognize one of their own is jammed up and not trying to draw attention to the fact.

“You know, I used to back trucks for a living and could get that right where you want. It wouldn’t take a minute?” With keen observation he read the hesitancy on my face to even briefly swap possession of my truck and trailer for his bicycle. He quickly added, “I live down at the other end of the neighborhood and was just headed over to Jill’s house to feed her animals while she is out of town.”

The addition of the appended set of “references” to his truck driving CV, plus the hours already spent in futility, and my daughter’s plea of, “Dad, let him try” was enough to tip my judgement. I opened the door, stepped into the street and let him slide in behind the wheel.

True to his word he smoothly glided the entire rig down the snowy hill, positioning it expertly in front of our driveway. As he stepped out I shook his hand, wounded ego in recovery mode by virtue of his grace and the relief of being done for the night.

“You need to let me give you something for this.” My mind scrambling to process how I would do this with a wallet I knew was running on empty.

He replied, “You know, I didn’t do this so you would pay me, but I have been homeless for the past few years and am just getting back on my feet. I finally have a car but no gas and it’s Christmas and I would surely appreciate anything you could do.”

Pulling my wallet out and handing him the few dollars I had, I proposed that he finish his errand and come back. I could then take him to his car so we could go to the gas station and fill his tank. He seemed both surprised and appreciative and within 20 minutes was back at my door.

Leaving his bike behind to claim later the three of us climbed into the car and headed off. We all introduced ourselves and expressed our mutual gratitude for the good turn to the evening. Well spoken and polite, David complimented us on our home following up with the one question that always puts a knot in my stomach. “What do you do for a living?”

I attempted a deflection by answering, “I am at that wonderful point in my life where I am starting to retire.” But he wasn’t having it.

“You look like you have done well. What did you do when you were working?” Too far from our destination to run the clock out with another stall. I would have to provide an answer.

Now, I love and am proud of what I have done for a living. It has been meaningful for me and is the perfect definition of the adage “love what you do and you will never have to work a day in your life”, but I have found that telling people you make your living by helping raise and give money away isn’t relatable for most. When I say it to folks not from that world I always imagine the lyrics of Dire Straits’ “Money for Nothing” starts running through their head.

Growing up I was taught working for a living involved spending your days, winter included, outdoors. And, as evidenced by both my father and grandfather’s hands, involved the risk of loss or damage to limbs or appendages. I have never been afraid of that kind of work when necessary. I even have a modestly shortened pinky finger to prove it. But its harshness did encourage me to finish college. And when I learned I could make as much or more by essentially talking for a living, I started moving my life in that direction.

Having had this conversation before I knew to keep it short and specific.

“I work in philanthropy. My career has been helping to raise and distribute money to worthy and charitable causes. I just finished helping raise funds to build a new YMCA and aquatic center and am currently working to rebuild a school district on an Indian reservation that hasn’t had a new building since the 1930’s.”

If he disapproved, it didn’t show, he just politely said, “Wow, I didn’t know people did that kind of thing.”

We arrived at the mobile home park where he was living and he directed me to his parked car. He got out as I waited to follow him.

He pulled into the station and was readying his tank when I parked, walked over, and put my card in the pump. He asked how much he should put in and I said to fill it. As he was finishing I went to the cash machine to get a few extra bucks. I folded up the bills and handed them to him as we prepared to say goodbye. We both thanked each other and he asked to be sure and let him know if anything came up where someone needed a good worker. I gave him a couple of suggestions, promised to think of more, and gave him my business card and told him to use me as a reference to anyone he needed. Almost as an afterthought I asked, “So David, are you from here?”

“No,” he answered, “I grew up on a cattle ranch my dad ran for a guy down on the Snake River”

The Snake River is over 1,000 miles long. It runs from Wyoming where it flows down from the Rockies high above Jackson and crosses the full width of southern Idaho before turning north and to carve Hell’s Canyon and define a portion of the Idaho Oregon border. Its final stretch turns west through the southwest corner of Washington where it empties into the Columbia River at Lake Wallula. At its closest point it’s about 500 miles from where my mom and dad homesteaded in 1945 after Dad was discharged from the Marines and came home from the Pacific. I know the name of just one ranch on the Snake River.

“Really? What ranch?”

“The Flying H. It doesn’t exist as such anymore. Not a lot of people ever knew about it.” he answered.

“Maurice and Kathleen Hitchcock’s place? Your dad was Maurice and Kathleen’s rancher?”

We shared a wide-eyed stare. I went on, “My grandfather was Maurice’s very first employee. He hired him as his mechanic and donkey puncher when Maurice was starting out as a gypo logger outside of Sisters Oregon. As he and Kathleen became more successful and Grandpa aged, he kept him on as his grounds keeper and handyman. My grandmother was their cook and housekeeper. The Hitchcock’s supported both long past their work life and safely into the next. They were among my family’s closest and most admired friends.”

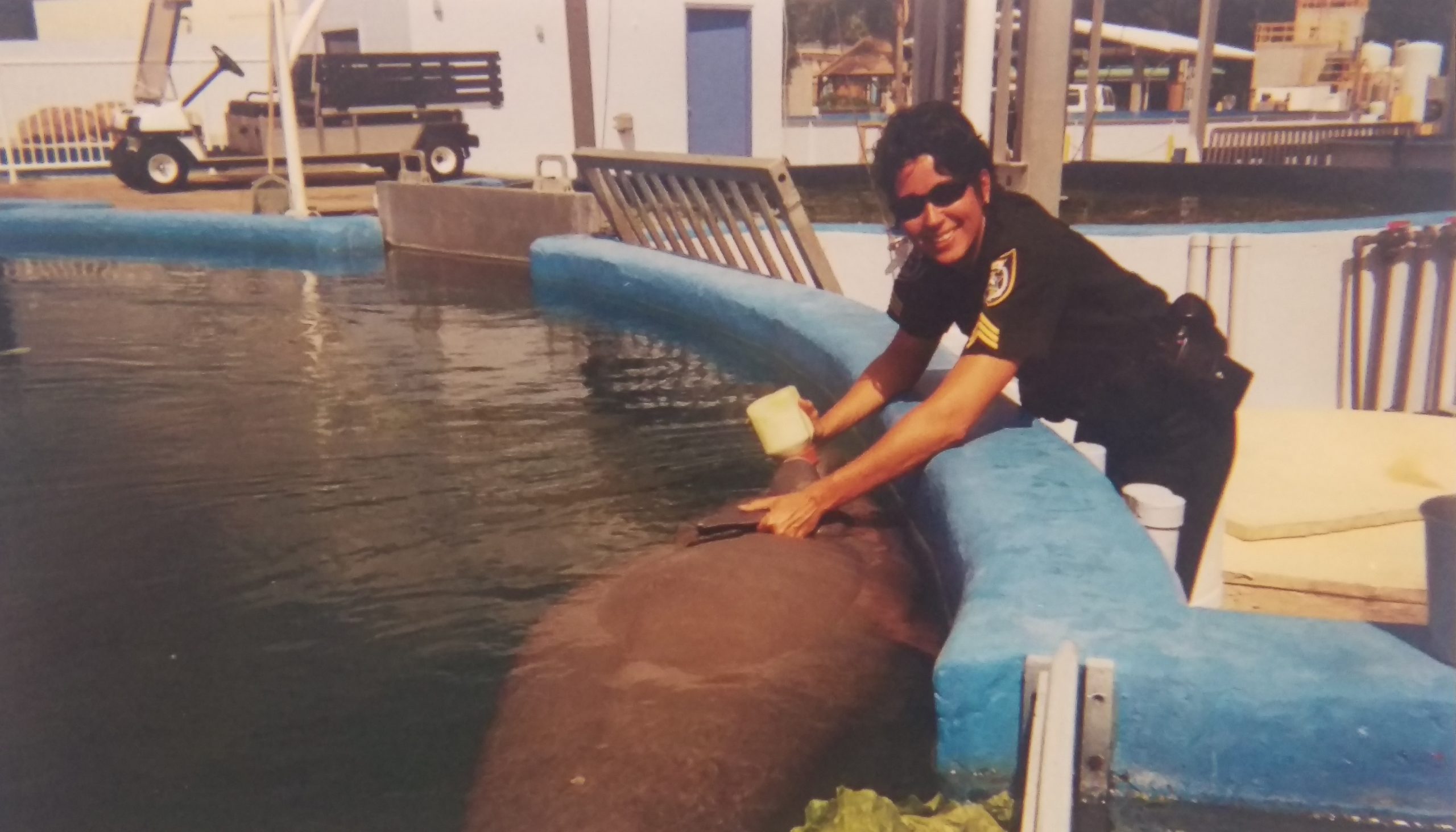

David told a similar story of how Maurice and Kathleen had paid for his dad’s college education, as they did for many students in the small town where their mills were located. After his Dad’s graduation he was hired by them to run their ranching operations. His dad sadly passed due to cancer in his mid-fifties. As an afterthought he added that his grandfather was the superintendent of schools in the town where the Hitchcock’s mill and home place were located.

Stunned again I stared back, “Vic and Thelma Anderson? You’re Vic and Thelma’s grandson? Your grandparents ran the school my siblings and I attended. In fact, I am pretty sure your father or uncle were classmates of my oldest brother. That school I told you I was trying to help rebuild? It’s your grandparents’ school.”

The only son of an only son, my father had, much to the embarrassment of his wife and children, the habit of striking up conversations with complete strangers in the hopes of finding a connection. When traveling he was known to look up family names in the local phone book and call perfect strangers on the off chance that they had been sitting around waiting to hear from him. When he would sometime be rewarded with some shred of a connection, often tenuous, we seldom shared his satisfaction. It was pure annoyance knowing his “success” would just breed more of the same behavior.

So it wasn’t so much the fact that David and I found a mutual connection, even as striking as it was, I grew up having that demonstrated to me on countless occasions. What was meaningful was the circumstance of our meeting and who we were connected by.

Vic and Thelma Anderson gave me, my siblings, and thousands of others the education that would become the foundation stone of their life. Maurice and Kathleen Hitchcock provided my family a toehold on wealth and inspired in me the secular importance of giving back. These couples shaped me in ways I never fully realized, acknowledged or thanked them for. I believe with no doubt it was the legacy of those influences, in both David and I, that guided us toward trusting each other in the middle of a dark, cold and snowy street at a time when we needed each other.

My grandfather, like all of us had a life filled with both fortune and misfortune. He was a gifted mechanic, who passed along those skills, and more than a few of his hand tools, to my father, who in turn gave them to me, who has endeavored to share them with my daughters. Like it or not, we are in large part what we inherit. When my grandfather went to work for Maurice it was at a time when, for a variety of reasons, losing his first wife at a young age, the depression, the habit of drink, he had not been able to hold a job and had lost much of what he had. I am not sure what kind of options Maurice had for prospective employees; all I know for certain is that they found and remained committed to each other for the rest of their lives. And I remain today one of the beneficiaries.

My prejudice and hypocrisy is not a product of superior insight. It’s my auto theism fooling me to believe my fortunes and misfortunes are of my sole god like creation. They aren’t. Our fortunes and misfortunes should not be what separate us. They should be what bind us together. Both in the moment and across the decades. Ignorance of that fact is the source of far too much needless suffering.

We moralize fortune and misfortune as virtue or vice when we would be better served by embracing its randomness. Fate has no cause. And even if it did it wouldn’t matter because the only important answer is to the question, “So now what are you going to do?”

The tangible legacy of the Hitchcock’s and Anderson’s lives in business and service, the lumber mills and schools, still exist today. As important as they are, it may not be the most valuable legacy they left us. Both couples, like many others of their day were exceptionally decent people. And as such it was in their character to look for, respect, and hold up the decency of others. I used to take that for granted but now know that I can’t. Decency has to be cultivated and we cultivate it in ourselves when we recognize, respect and cultivate it in others.

As our conversation drew to a close we shook hands again, wished each other a Merry Christmas and headed for our cars. As I was backing out, he apparently unfolded and counted the bills I gave him and came back over and tapped on my window. As I rolled it down he said he just wanted to say thanks one more time and share a final thought, “You know I think tonight just proves the point that sometimes it pays to go backward in life.”