Catching Up to COVID

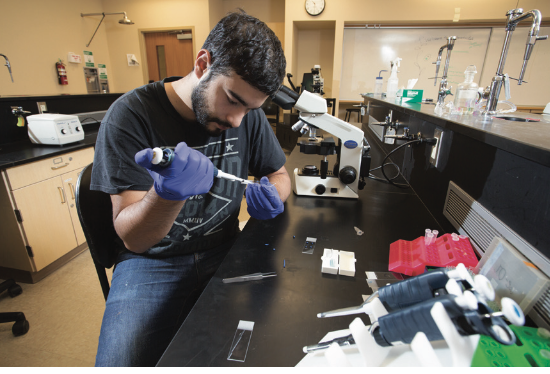

Nursing students’ COVID research helps community organizations understand the virus’s impact on those they serve

When nursing student Tashaé Gomez-Jones was preparing for her community health rotation at the Yakima Union Gospel Mission, she had no idea how impactful her work would be for the non-profit and how much it would shape her view on her future career.

Gomez-Jones, a senior who graduates in May, spent five weeks conducting a COVID-19 survey with homeless men and women staying at the Mission in the fall. She is one of several students enlisted by Yakima Valley organizations to conduct client and community surveys about COVID. Her classmate Heather Delozier, also a senior, took part in the same rotation and research. Similarly, Almarae Swan- Tsoodle, a junior majoring in nursing, works with the Yakama Nation and Fred Hutch on a COVID-19 patient survey. For both organizations, the goal was, and is, to better understand the impact of the virus on their communities as a way to improve services now and in the event of future health crises.

COVID AND THE HOMELESS

A few weeks before Gomez-Jones and Delozier started their practicum, the Yakima Health District approached the Mission with a request to conduct mandatory COVID testing of its clients. It was something the Mission was hesitant to do.

“The people who use the Mission services are already pretty fragile and distrustful,” said Gomez- Jones. “They have some pretty significant barriers, such as felonies, mental illness and immigration status that makes them wary of outsiders. They (Mission Administration) were afraid that mandatory testing would put up a barrier that would keep homeless people from seeking services.”

That, said Gomez-Jones, could have had an equally devastating effect. The myriad of issues that homeless men and women face—malnutrition, lack of healthcare, exposure to the elements, drug and alcohol abuse, mental illness—already put them at high risk. For so many of these people, the Mission is the last line of defense that keeps them out of harm’s reach. Putting up a barrier to keep fragile people from bare necessity help could have devastating effects. On the other hand, the Mission also needed a better understanding of their clientele’s knowledge about COVID-19 and their personal safety practices to ensure the safety of all who seek help there.

Gomez-Jones and Delozier started their rotation at the perfect moment. Under the Mission’s directive, they developed a client survey that asked some basic information: What do you know about COVID? Where did you get your information? Have you been vaccinated, or are you willing to be vaccinated? If you got COVID, would you be willing to quarantine at the Mission?

Creating the survey was the easy part. Next, the women had to build enough trust with the clients to get them to agree to share their stories.

“I wasn’t sure how it was going to work,” said Gomez-Jones. “Our biggest fear was we were outsiders. We were afraid they wouldn’t trust us enough to really open up.”

Every day, the pair would approach the people they saw at the Mission. They’d explain who they were, what they were doing, and ask if they would be interested in participating. Some agreed to answer their questions right away; others took a little more time to build up enough trust. As word spread through the Mission about the two Heritage nursing students, clients began to approach them.

“We found the clients very receptive,” she said. “For so many of these people, nobody listens to them or cares about them. Even when they go to the ER to seek help, they are treated poorly. Asking them their opinion made them feel valued.”

As the days progressed, Gomez-Jones and Delozier’s role with the people at the Mission began to change.

“We started to have clients come up to us to seek help with their physical ailments,” she said. “They’d ask us to help them connect with a clinic or help them find rides to get to their treatment. We even had a few instances where they’d mention a medical concern that ended up being a pretty serious, life-threatening issue during our conversation with a client. We would never have known about it if we were not talking to them.”

Delozier credits these interactions, where they helped clients fill an unmet need, as key to helping them break down barriers and build the relationship that ultimately led to getting responses to their survey questions.

“It takes patience to work with this population of people. We were there at the Mission three days a week, all day long. They saw us there and would sometimes ask us for help with things like getting them socks, and we’d do it,” she said. “It really helped us build a rapport with them.”

In the end, Gomez-Jones and Delozier completed about 60 surveys in the five weeks they were at the Mission. They found an overall willingness among the responders to get vaccinated and quarantine if they were infected. About half of the respondents were already vaccinated, and they were among the most passionate about the need for vaccines, especially given the vulnerability of the homeless population. Moreover, those who had not yet been vaccinated were mostly open to the idea of getting the vaccine but were still a bit unsure because they didn’t have enough information on its safety. The lack of information was not surprising, said Gomez-Jones, given that most reported that everything they know about COVID was gleaned from what they read on signs posted on the doors of businesses they walked by.

For Gomez-Jones, the experience was eye-opening and personally rewarding.

“I was most surprised by how welcoming the clients were and how happy I felt being there,” she said. “Before this, I hadn’t had a lot of interactions with homeless people, and there are lots of stereotypes about homelessness.”

Delozier’s experience was similar. Initially, she was apprehensive about the assignment, maybe even a little scared. In the end, she found it extremely rewarding.

“We got to know these people on a human level,” she said. “We came to understand their struggles. How they really try, fail, and try again, and how important it is to be encouraging. I think the experience made me a more empathetic nurse.”

YAKAMA NATION COVID RESPONSE

As COVID-19 spread throughout the Yakima Valley, the Yakama Nation was particularly hard hit. By the end of December 2021, the tribe of 8,800 enrolled members had seen 2,487 known cases and 61 deaths from the virus.

In the last half of 2021, Fred Hutch approached Indian Health Services on the Yakama Nation to partner on a survey project that would look at COVID-19 patients, past and present, to get a feel for the effectiveness of services accessed. They wanted to identify areas that worked well, those that could be improved, and areas where resources should be directed. The idea was not so much on how to respond to COVID but rather to help build a crisis action plan for future events.

Swan-Tsoodle joined the project late in 2021. She is enrolled Yakama and has seen firsthand just how devastating the virus has been for families on the reservation. It was important to her to be part of something that brought solutions and healing to her community.

“Living on the reservation, I know that if you want to make a change, you have to involve your people. You have to hear from them and ask questions to fully understand the problem before you can find solutions,” she said. “I want to be someone who helps us all move forward and break negative cycles.”

“Living on the reservation, I know that if you want to make a change, you have to involve your people. You have to hear from them and ask questions to fully understand the problem before you can find solutions,” she said. “I want to be someone who helps us all move forward and break negative cycles.”

The project involves collecting data from phone interviews with patients who were or are COVID positive. Patients are identified and recommended to the study by medical providers at Indian Health Services in Toppenish. Swan-Tsoodle contacts each individual, explains the program to them, and invites them to participate. While it focuses primarily on the tribal community, it is open to anyone living within the boundaries of the Yakama Nation reservation. Participants are asked about their experiences with COVID, in particular how their life and that of their family were impacted. Questions are not limited to healthcare but include conversations about topics ranging from economic and social impacts to food and job security.

“One of the things that’s been most eye-opening is how disruptive this virus is to the family and our entire society, in unexpected ways,” said Swan- Tsoodle. “We talk to people who were once fairly well off, then one person in their family got sick. It was the beginning of a downhill spiral. Suddenly people were not able to work. They have no income, no resources. Their lives were on a precarious teeter-totter, and the virus is what pushed them over the edge.”

The project is in its very early stages, explained Swan- Tsoodle, and the number of participants to date is nowhere near a statistically representative count to give researchers a clear picture. However, the work is ongoing and is expected to bring in more data over time. Unlike her peers who did similar work at the Mission, Swan-Tsoodle works part-time for the project outside of her nursing studies and will continue with the research as it progresses.

EXPERIENCES THAT BRIDGE ACADEMICS AND CAREERS

The kind of hands-on, real-life experiences that Swan-Tsoodle, Gomez-Jones and Delozier were part of is a key element in many of Heritage’s academic programs. Not only do they give students valuable work experience while completing their studies, but they can also introduce them to previously undiscovered career paths, such as the case with Gomez-Jones.

“Heritage University places a great emphasis on students and their education through place-based experiential learning experiences,” said Dr. Maxine Janis, Nursing professor and president’s liaison for Native American affairs. “The opportunity for career discovery while in college is central. Connecting learning to careers can form a strong foundation for our students in every degree field. It provides context to the subjects they are learning in the classroom, exposes them to the myriad of opportunities they can pursue after they earn their degrees, and helps them make professional connections that will serve them throughout their careers.”

This was certainly the case for Gomez-Jones.

“Going into this, I had been unsure about my career,” she said. “I had done some of my hospital rotations but didn’t

really see myself working in that environment. Between my experience at the Mission and the mental health rotation, I found something I can be passionate about. I can definitely see myself working in mental health or community health in some capacity after I graduate.”